Who is hungry in Canada?

FromThe Canadian Association of Food Banks

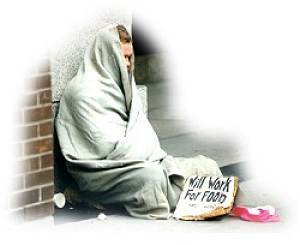

In Canada, hunger is largely a hidden problem. Many Canadians are simply not aware that large numbers of children, women and men in this country often go to bed hungry.

While anyone is at risk of food insecurity at some point in their lives, certain groups are particularly vulnerable:

Welfare Recipients

People receiving welfare assistance as their primary source of income continue to make up the largest group of food bank users. This year, 51.6% of food bank clients in Canada were receiving welfare. This suggests that welfare rates in Canada do not do enough to ensure food security for low-income Canadians. According to the National Council of Welfare, welfare rates across Canada continue to fall below the poverty lines.

Working Poor

People with jobs constitute the second largest group of food bank clients, at 13.1%. Anecdotal evidence in the HungerCount 2005 report shows that the majority of food bank clients with jobs are employed at low wages. The expansion of the low-wage economy has generated more working poor who, even with full-time jobs, are unable to meet basic needs for themselves and their families.

Persons With Disabilities

Those receiving disability support have made up the third largest group of food bank clients in the last four years, according to successive HungerCount surveys. It is just one more example of the broader crisis of inadequate social assistance in Canada. Disability support is clearly not enough to help clients feed themselves. If current disability programs and rates do not improve we expect to see a rise in food insecurity among this demographic, since Canada has a rapidly aging society and life expectancy is increasing.

Seniors

Seniors accessing food banks across Canada is a sad reality. HungerCount 2005 reports that seniors accounted for 7.1% of food bank users in a typical month of 2005. This is an increase from the previous year when 6.4% of food bank clients were seniors.

Children

Children continue to be over-represented among food bank recipients in Canada. This year, 40.7% of food bank clients were under 18. Child poverty has not improved since 1989, the year when Canada made an all-party resolution to end child poverty. Child poverty is directly tied to the level of household income. Among food bank clients, families with children make up more than 50% of recipients.

Lone Mothers

Lone mothers and their children are still one of Canada's most economically vulnerable groups. It is likely that many of the food bank users who are sole parents (29.5%), as reported in HungerCount 2005, are women: according to Statistics Canada, the majority of single-parent or lone-parent families are headed by women (85% or 1 in 4 of Canada's lone-parent families).

Solutions

Hunger, as a symptom of poverty, is a structural problem. Sustainable solutions to hunger and poverty require a mix of system-based policies aimed at improving the incomes and income security of poor Canadians, such as raising social assistance rates and minimum wages, improving access to employment insurance and developing a national child care system. HungerCount 2005 outlines specific public policy recommendations to governments in eradicating domestic hunger.

Benefits for low-income seniors are going up

The Guaranteed Income Supplement (GIS), the Allowance and the Allowance for the survivor are going up 7%. The increase will be phased in over two years. In January 2006, GIS and Allowance payments will go up $18 a month for single seniors and $29 a month for couples. In January 2007, payments will increase again by the same amount. If you think you might be eligible for one of these benefits, call 1-800-277-9914 (toll-free) or contact the regional coordinator nearest you. Fact sheets and posters are also available upon request. For more information on seniors' benefits visit the Service Canada website.

Food bank use by B.C. children up 42 per cent

FromCTV.ca

VICTORIA — A national report on the use of food banks by children in Canada has put British Columbia on its trend watch.

The B.C. Liberal government said it's concerned about the results which found 41.7 per cent more children needed emergency food in B.C. in 2004 over 2003- some 8,000 more kids. Human Resources Minister Susan Brice, however, said the conclusions in the Canadian Association of Food Banks' annual report reflect a North American problem.

The B.C. Liberal government said it's concerned about the results which found 41.7 per cent more children needed emergency food in B.C. in 2004 over 2003- some 8,000 more kids. Human Resources Minister Susan Brice, however, said the conclusions in the Canadian Association of Food Banks' annual report reflect a North American problem. The association's annual national HungerCount survey also found that in Saskatchewan nearly 2,000 more children needed food banks in 2004, an increase of 24 per cent from 2003.

Child Poverty In Canada- An Overview

From Free The Children.org

Many people mistakenly assume that child poverty is a challenge only people in developing countries are facing. This is sadly untrue. In Canada, the situation of child poverty has gone from bad to worse. UNICEF’s report on Child Poverty in developed countries ranks Canada near the bottom for children’s well-being, at 17 out of 23 countries. This is unacceptable for a country that prides itself on being consistently chosen as the best place in the world to live.

• Canada is one of the richest countries in the world. However, about 1,400,000 of its children live in poverty (almost one and a half million). Children of single parents and those of aboriginal descent have suffered the most.

• Children are poor because they live in disadvantaged families. The way to end child poverty is to allow families the ability to support themselves in a meaningful way. The last thing a parent wants is to have their children go hungry.

• Single mothers and their children experience the worst levels of poverty. 81% of single mothers with children under the age of 7 live in poverty. Countries such as Sweden and France provide far greater help to single mothers so that they and their children do not live in poverty.

• Food banks: A U.N. Human Rights committee noted that the number of food banks in Canada grew from 75 in 1984 to 625 by 1998.

• A U.N. Human Rights Committee criticized Canada for adopting policies that have increased poverty and homelessness among many vulnerable groups (such as children and women) during a time of strong economic growth and increasing affluence.

• The federal government says that its Child Tax Benefit helps poor children. But the benefit is far too low and the poorest children are disqualified from receiving it. Children living in families receiving welfare - who are the poorest children in Canada - have the benefit taken away from them by their provincial government. This is wrong and must be ended. Apart from Newfoundland and New Brunswick, the poorest children and their families receive no help from the Child Tax Benefit.

• Children of full-time working parents make up almost 30% of poor children in Canada. Their parents do not get paid a living wage. Workers in developing countries making shoes for Nike or goods for Wal-Mart should be paid a living wage. Workers in Canada should also receive a living wage. In the United States 32 cities have passed bylaws requiring that all city contractors pay their workers a living wage. Perhaps Canadian cities and provinces should be asked to make the same commitment.

• Each province and the federal government have minimum wage laws. All workers must be paid at least the minimum wage. But, taking account of inflation, these minimum wages are 25-to-30% lower today than they were twenty years ago.

The UN Convention on the Rights of the Child (UNCRC)

Canada has ratified the United Nations Convention on the Rights of the Child. In doing so, it is obligated to provide basic human rights to all children. The Convention, for example, obligates Canada to provide an adequate standard of living for all children.

But hundreds of thousands of Canadians are going hungry and have to go to food banks because they do not have enough to eat. It is a sad fact that almost half of the people using food banks are children.

Canada's Charter of Rights and Freedoms

Canada's Constitution includes a Charter of Rights and Freedoms that guarantees every Canadian security of the person. People who live in poverty do not have security of the person. If they live in hunger, their health and their lives are at risk. If they are homeless, they do not have physical or mental security.Poverty means that people do not enjoy their basic human rights.

The UN currently ranks Canada 17th out of 23 industrialized countries – seventh from the bottom – when it comes to child poverty

Child Poverty UN Report

By Mark Nichols

From Maclean's

Candace Warner, a jobless single parent, lives with her sons - two-month-old Keo and 1 ½-year-old Skai - in Winnipeg's run-down Wolseley district. The product of an impoverished background, Candace, 24, struggles to pay the apartment rent and feed and care for her children on about $1,000 a month in social assistance. "My sons need new clothes and things that I can't buy," she says, "because I don't have the money." With Canada's once sturdy social safety net badly frayed, the plight of Candace and her kids is not unusual.

According to a study released last week by the United Nations Children's Fund - UNICEF (the organization long ago changed its name, but kept the old acronym) - 15.5 per cent of Canadians under 18 live in poverty. That relegated Canada to 17th place in a ranking of 23 industrialized nations and prompted demands for action. "Politicians talk about eradicating child poverty," said Jean-Marie Nadeau, executive assistant at the New Brunswick Federation of Labour. "Then they shut their big doors and the young are forgotten."

As it happened, publication of the UN study coincided with a Statistics Canada report showing that a buoyant economy finally pushed 1998 family incomes past levels recorded before the recession of the early 1990s, with after-tax family incomes averaging $49,626. The numbers also showed the gap between low-income and affluent Canadians steadily widening, leaving 3.7 million Canadians in straitened circumstances.

Income disparities figured prominently in the UNICEF study, which estimated that 47 million impoverished children live in the world's 23 richest countries. The report found the lowest rates of child poverty among northern European countries with strong traditions of wealth redistribution. Sweden - with only 2.6 per cent of its children living in poverty - had the lowest rate, while Canada ranked behind France, Germany, Hungary and Japan, but ahead of Britain, Italy, the United States and Mexico, in last place with a 26.2-per-cent child poverty rate.

The sometimes surprising findings were partly due to methodology - the rankings were based on "relative poverty," defined as household income that is less than half of the national median. That meant nations like the Czech Republic and Poland, with high overall poverty rates, came out ahead of Canada, Britain and the United States, where higher average incomes and income disparities make more people relatively poor.

"Canada reflects poorly in a relative measurement," said Marta Morgan, director of children's policy at Human Resources Development Canada, "because middle incomes in this country are quite high." Even so, when social advocacy groups use StatsCan's low-income cutoff as a measure of poverty, they generally estimate there were about 1.4 million poor children in Canada in 1997 - a child poverty rate of 19.8 per cent that is well above UNICEF's.

The study's authors argued that even when children from families with limited resources have the necessities of life, they suffer by being excluded from normal childhood activities. Linda Rowe, a single Halifax mother who stretches aid of about $1,400 a month to support herself and two young sons, knows they are feeling that pinch. "Right now, I'm trying to borrow $20 so my kids can go on a school trip," she says.

With the years of stringent budget-cutting behind them, Ottawa and some provinces have started to rebuild social supports that benefit low-income families. Finance Minister Paul Martin's February budget reduced taxes for families with children and earmarked $2.5 billion in additional funding for Ottawa's child tax benefit, which currently pays up to about $160 a month for children in low-income families. And after nearly three years of wrangling, federal-provincial talks on a proposed National Children's Agenda - that could usher in early childhood development and child-care programs - appeared to be moving ahead, with ministers agreeing to draft a policy framework by the fall.

Even so, some provinces still insist that Ottawa will have to restore billions of dollars in lost health and social funding before the agenda becomes a reality - a stumbling block that could hold up long-overdue measures to help Canada's children.

Poor Kids in Developed Nations

Percentage of children living in "relative" poverty

(household income below 50 per cent of national median):

Sweden: 2.6%

Norway: 3.9%

Finland: 4.3%

Belgium: 4.4%

Luxembourg: 4.5%

Denmark: 5.1%

Czech Republic: 5.9%

Netherlands: 7.7%

France: 7.9%

Hungary: 10.3%

Germany: 10.7%

Japan: 12.2%

Spain: 12.3%

Greece: 12.3%

Australia: 12.6%

Poland: 15.4%

Canada: 15.5%

Ireland: 16.8%

Turkey: 19.7%

Britain: 19.8%

Italy: 20.5%

United States: 22.4%

Mexico: 26.2%

Source: UNICEF

Noam Chomsky on Microsoft and Corporate

Control of the Internet(excerpt)

By Anna Couey and Joshua Karliner

From CorpWatch

CW: Do you think the whole monopoly issue is something to be concerned about?

NC: These are oligopolies; they are small groups of highly concentrated power systems which are integrated with one another. If one of them were to get total control of some system, other powers probably wouldn't allow it. In fact, that's what you're seeing.

CW: So, you don't think Bill Gates is a latter-day John D. Rockefeller?

NC: John D. Rockefeller wasn't a monopolist. Standard Oil didn't run the whole industry; they tried. But other power centers simply don't want to allow that amount of power to one of them.

CW: Then in fact, maybe there is a parallel there between Gates and Rockefeller, or not?

NC: Think of the feudal system. You had kings and princes and bishops and lords and so on. They for the most part did not want power to be totally concentrated, they didn't want total tyrants. They each had their fiefdoms they wanted to maintain in a system of highly concentrated power. They just wanted to make sure the population, the rabble so-called, wouldn't be part of it. It's for this reason the question of monopoly -- I don't want to say it's not important -- but it's by no means the core of the issue.

It is indeed unlikely that any pure monopoly could be sustained. Remember that this changing technology that they're talking about is overwhelmingly technology that's developed at public initiative and public expense. Like the Internet after all, 30 years of development by the public then handed over to private power. That's market capitalism.

CW: How has that transfer from the public to the private sphere changed the Internet?

NC: As long as the Internet was under control of the Pentagon, it was free. People could use it freely [for] information sharing. That remained true when it stayed within the state sector of the National Science Foundation.

As late as about 1994, people like say, Bill Gates, had no interest in the Internet. He wouldn't even go to conferences about it, because he didn't see a way to make a profit from it. Now it's being handed over to private corporations, and they tell you pretty much what they want to do. They want to take large parts of the Internet and cut it out of the public domain altogether, turn it into intranets, which are fenced off with firewalls, and used simply for internal corporate operations.

They want to control access, and that's a large part of Microsoft's efforts: control access in such a way that people who access the Internet will be guided to things that *they* want, like home marketing service, or diversion, or something or other. If you really know exactly what you want to find, and have enough information and energy, you may be able to find what you want. But they want to make that as difficult as possible. And that's perfectly natural. If you were on the board of directors of Microsoft, sure, that's what you'd try to do.

Well, you know, these things don't *have* to happen. The public institution created a public entity which can be kept under public control. But that's going to mean a lot of hard work at every level, from Congress down to local organizations, unions, other citizens' groups which will struggle against it in all the usual ways.

CW: What would it look like if it were under public control?

NC: It would look like it did before, except much more accessible because more people would have access to it. And with no constraints. People could just use it freely. That has been done, as long as it was in the public domain. It wasn't perfect, but it had more or less the right kind of structure. That's what Microsoft and others want to destroy.

CW: And when you say that, you're referring to the Internet as it was 15 years ago.

NC: We're specifically talking about the Internet. But more generally the media has for most of this century, and increasingly in recent years, been under corporate power. But that's not always been the case. It doesn't have to be the case. We don't have to go back very far to find differences. As recently as the 1950s, there were about 800 labor newspapers reaching 20-30 million people a week, with a very different point of view. You go back further, the community-based and labor-based and other media were basically on par with the corporate media early in this century. These are not laws of nature, they're just the results of high concentration of power granted by the state through judicial activism and other private pressure, which can be reversed and overcome.

CW: So take the increasing concentration in the technology that we're looking at with Microsoft and some of these other companies, and compare it with recent mergers in the defense, media, insurance, and banking industries, and especially the context of globalization . Are we looking at a new stage in global capitalism, or is this just a continuation of business as usual?

NC: By gross measures, contemporary globalization is bringing the world back to what it was about a century ago. In the early part of the century, under basically British domination and the gold standard, if you look at the amount of trade, and then the financial flow, and so on, relative to the size of the economy, we're pretty much returning to that now, after a decline between the two World Wars.

Now there are some differences. For example, the speed of financial transactions has been much enhanced in the last 25 years through the so-called telecommunications revolution, which was a revolution largely within the state sector. Most of the system was designed, developed, and maintained at public expense, then handed over to private profit.

State actions also broke down the post-war international economic system, the Bretton Woods system in the early 1970s. It was dismantled by Richard Nixon, with US and British initiative primarily. The system of regulation of capital flows was dismantled, and that, along with the state-initiated telecommunications revolution led to an enormous explosion of speculative capital flow, which is now well over a trillion dollars a day, and is mostly non-productive. If you go back to around 1970, international capital flows were about 90% related to the real economy, like trade and investment. By now, at most a few percent are related to the real economy. Most have to do with financial manipulations, speculations against currencies, things which are really destructive to the economy. And that is a change that wasn't true, not only wasn't true 100 years ago, it wasn't true 40 years ago. So there are changes. And you can see their effects.

That's surely part of the reason for the fact that the recent period, the last 25 years, has been a period of unusually slow economic growth, of low productivity growth, of stagnation or decline of wages and incomes for probably two thirds of the population, even in a rich country like this. And enormously high profits for a very small part of the population. And it's worse in the Third World.

You can read in the New York Times, the lead article in the "Week in Review" yesterday, Sunday, April 12, that America is prospering and happy. And you look at the Americans they're talking about, it turns out it's not the roughly two thirds of the population whose incomes are stagnating or declining, it's the people who own stock. So, ok, they're undoubtedly doing great, except that about 1% of households have about 50% of the stock, and it's roughly the same with other assets. Most of the rest is owned by the top 10% of the population. So sure, America is happy, and America is prosperous, if America means what the New York Times means by it. They're the narrow set of elites that they speak for and to.

CW: We are curious about this potential for many-to-many communications, and the fact that software, as a way of doing things carries cultural values, and impacts language and perception. And what kind of impacts there are around having technology being developed by corporations such as Microsoft.

NC: I don't think there's really any answer to that. It depends who's participating, who's active, who's influencing the direction of things, and so on. If it's being influenced and controlled by the Disney Corporation and others it will reflect their interests. If there is largely public initiative, then it will reflect public interests.

CW: So it gets back to the question of taking it back.

NC: That's the question. Ultimately it's a question of whether democracy's going to be allowed to exist, and to what extent. And it's entirely natural that the business world, along with the state, which they largely dominate, would want to limit democracy. It threatens them. It always has been threatening. That's why we have a huge public relations industry dedicated to, as they put it, controlling the public mind.

CW: What kinds of things can people do to try to expand and reclaim democracy and the public space from corporations?

NC: Well, the first thing they have to do is find out what's happening to them. So if you have none of that information, you can't do much. For example, it's impossible to oppose, say, the Multilateral Agreement on Investment, if you don't know it exists. That's the point of the secrecy. You can't oppose the specific form of globalization that's taking place, unless you understand it. You'd have to not only read the headlines which say market economy's triumphed, but you also have to read Alan Greenspan, the head of the Federal Reserve, when he's talking internally; when he says, look the health of the economy depends on a wonderful achievement that we've brought about, namely "worker insecurity." That's his term. Worker insecurity--that is not knowing if you're going to have a job tomorrow. It is a great boon for the health of the economy because it keeps wages down. It's great: it keeps profits up and wages down.

Well, unless people know those things, they can't do much about them. So the first thing that has to be done is to create for ourselves, for the population, systems of interchange, interaction, and so on. Like CorpWatch, Public Citizen, other popular groupings, which provide to the public the kinds of information and understanding, that they won't otherwise have. After that they have to struggle against it, in lots of ways which are open to them. It can be done right through pressure on Congress, or demonstrations, or creation of alternative institutions. And it should aim, in my opinion, not just at narrow questions, like preventing monopoly, but also at deeper questions, like why do private tyrannies have rights altogether?

CW: What do you think about the potential of all the alternative media that's burgeoning on the Internet, given the current trends?

NC: That's a matter for action, not for speculation. It's like asking 40 years ago what's the likelihood that we'd have a minimal health care system like Medicare? These things happen if people struggle for them. The business world, Microsoft, they're highly class conscious. They're basically vulgar marxists, who see themselves engaged in a bitter class struggle. Of course they're always going to be at it. The question is whether they have that field to themselves. And the deeper question is whether they should be allowed to participate; I don't think they should.

Art: For the Common Delight

by Dee Axelrod

From Yes!

After a century of art for art’s sake, art in the last decade has been increasingly giving voice to the silenced, illuminating complex political issues, and bringing joy to the public square.

While the last 10 years have seen the weakening of funding to individual artists and the end of many alternative venues for showing art, a global art scene is thriving. The broadening and democratization of mainstream art, largely driven by the Internet, has helped reshape the aesthetic landscape from a New York-centric, gallery-driven scene to a thriving online global arts community.

In 1995, widespread access to the Internet produced a dazzling explosion of opportunities for artists to connect with practitioners from all over the world. Suddenly, in a single afternoon, an artist could “visit” a Prague printshop, view the Conesisters’ collection of early Modernist works at the Baltimore Museum, chat with a collective of feminist artists in New Zealand, submit work to an abundance of shows worldwide—or show and sell from her own website.

The Internet has created not just virtual art spaces but new opportunities for showing physical art in the real world, giving new scope to DIY (do it yourself) ingenuity. A traveling exhibit, for example, that would once have been organized by curators might now be artist-created and controlled—and feature works from all over the world.

One such show, organized online, opened in Milwaukee in 2001, featuring mixed media works ranging from Chicago artist Carlos Cortez’ woodcut posters for Industrial Workers of the World (I.W.W.) to Beehive Design Collective artists Kehban Grifter and Juan Manchu’s images in collaboration with several Colombian communities. By August 2005, the exhibit had been shown in 27 cities and traveled more than 25,000 miles, aided by a website, www.drawingresistance.org, that became a virtual gathering place. “Drawing Resistance” depended on publicity and fund-raising from each local venue.

The capacity to stay connected online has helped power a healthy diaspora of artists to places besides New York, just as the Internet emphasis on communication has encouraged artists toward collective art activities that make an end run around market influences.

It has also encouraged new forms of arts education. The Beehive Collective (www.beehivecollective.org), an ongoing, decentralized collaboration of anonymous “bees,” has made it its mission “to cross-pollinate the grassroots” by producing images that anyone is free to take and use. Among other projects, the “hive” delivers some 200 lectures per year on globalization and promotes collaborations between the visual and literary arts.

Community arts programs—curricula for teaching a more socially engaged art—emerged at such campuses as the Institute for Social Ecology and Goddard College, both in Plainfield, Vermont.

A group of 60 “eco artists” who gathered at the 1998 College Art Association meeting in L.A. formed an ongoing network of artists concerned with preserving and restoring the natural world.

One such project, completed in June 2005, is “Three Rivers Second Nature”—an analysis of three river systems and 53 streams of Allegheny County, Pennsylvania initiated by Carnegie Mellon University’s Studio for Creative Inquiry. A team of artists and researchers, headed by Tim Collins and Reiko Goto, synthesized information gathered from historians, landscape architects, geographic information systems specialists, botanists, engineers, and water-policy experts to map the region’s natural history, analyze water use, and consider stream restoration. On completion of the project, the team presented their findings to the public.

Meanwhile, the traditional notion of public art—a discrete object made without much consideration for a particular place—has undergone a transformation that reflects artists’ deepening understanding of what it means to work in community.

Artists first began to take into account the history and ecology of a particular site in the early 1970s. A natural next step was to consult with community members, perhaps eliciting their ideas and even some contributions. Over the last decade, a public art has emerged that seeks to place the creative process wholly in the hands of the community, with the artist in the role of facilitator, helping to draw forth a community’s stories. Community has been defined broadly to include such marginalized groups as inmates and shelter inhabitants.

But of all recent developments, it may be the emergence of artist-activists in their 20s that is most exciting. A different breed from past art school graduates competing to become “art stars,” these young people make art in service to social change. They do “reclamation art” projects at degraded sites. They help create dialogue among polarized groups. They work to foster a sense of community.

They are the hopeful future of art.

Related Web Sites

www.ecoartnetwork.org - A Web site dedicated to ecological art and the artists who create it. Here you can find sites of the artists participating in the movement.

www.greenmuseum.org - More resources on the culture of eco-art and the people who practice its ideals. Lots of information, including interactive WIKIs for educational resources and discussion groups.

www.artsforchange.org – Using art as a tool for healing and social change. The creation of Beverly Naidus.

www.communityarts.net – Promoting information exchange, research and critical dialogue within the field of community-based art including programs that teach community-based art.

www.goddard.edu – Join an MFA program in Interdisciplinary Arts that has a focus on art for social change, healing, spiritual growth and a required community art practicum.

Hope for year-round veggies growing in Elie[Manitoba, Canada]

BY Angela Brown

From The Central Plains Herald 2005

ELIE — A plump, freshly grown tomato is a delight for many, but in the middle of a Manitoba winter, it is an especially rare treat. That may be about to change. A garden in Elie has been able to withstand even a harsh Manitoba winter and produce tomatoes, cucumbers and watermelons out of season. Three special solar-powered greenhouses are making all of that possible. “I started in February and can keep them all winter until Christmas,” said Wenkai Liu, who started his unique agricultural business at Elie about a year ago. “I seeded again in the end of June, so they’ll by ready for Christmas.”

Smiling with pride as he gazes over a bountiful crop of tomatoes in one of the greenhouses, Liu said a great deal of work went into the business from ordering the greenhouses, arranging for a technician to come from China to provide his expertise, to the day-to-day management of the operation. As well, Liu employs six workers for the greenhouses and his 5.6-hectare farm, and said he could still do with more help.

The three greenhouses produce a total of 0.4 hectares or an average of 9,000 kilograms each of crop every six months. The total cost for each greenhouse is about $14,000.Liu uses solar energy to heat his greenhouses, having modified the conventional greenhouse to harness the sun’s heat and use it more efficiently over a longer period of time.

In order to grow vegetables in Manitoba’s cold winter, Liu had his unique greenhouses shipped from China as none were available here.

What makes them so effective is their insulating properties. Each greenhouse is 207 square metres in size and its north wall is insulated with 15 centimetres each of sand and fibreglass, and covered with metal panels.

During the day, the sun strikes the metal wall and heat is absorbed into the sand insulation. The sand holds the heat and releases it into the room at night to maintain the temperature in the greenhouse. A thermal blanket is also rolled over the greenhouse to keep the building warm. “The temperature is checked every day,” Liu said. “The safe temperature is 25 degrees Celsius to 28 degrees Celsius for tomatoes.” At night, Liu attempts to maintain a temperature of 15 degrees Celsius.

“I’m trying to get that, but it’s difficult,” Liu said, pondering the situation.

Like a watchful mother, Liu looks over the proud crop of beefsteak tomatoes on their tall vines that reflect a mature produce. Near the entrance to the greenhouse, young seedlings of tomatoes and cucumbers emerge in a verdant patchwork from a separate garden.

The soil is dark and rich-looking. It has been fertilized with organic manure and covered with plastic, out of which the plants are bursting forth from the ground.

No need to irrigate, Liu remarked. The plastic seals the moisture in. “I don’t even spend time to weed,” he chuckled. “There’s no weeds.” Liu has a glimmer in his eye and for a good reason. He wants to share his secret. One of Liu’s three greenhouses at Elie is the subject of a research project involving University of Manitoba and Manitoba Hydro. Its two aims are to reduce the cost of heating a greenhouse in winter and to provide a year-round market for greenhouse-grown vegetables in this province. “In comparison with the traditional greenhouse, the solar greenhouse is about 15 degrees warmer,” said Qiang Zhang, a University of Manitoba biosystems engineer heading the project.

Agri-Food Research and Development Initiative (ARDI), a joint federal and provincial program through the Departments of Agriculture, helped fund the project which will run for another year at Elie. There are also plans to test supplemental electric heaters to keep the research greenhouse warm during the coldest days of the year in December and January when the temperatures can drops to -35? Celsius or lower. However, the project was started in February without using any additional electric heating and has been successful. “I’m very impressed with the results,” said Zhang. Liu noted he can use wood stoves to increase the warmth in his other two greenhouses when temperatures drop too low.

Ray Boris, an agricultural engineer with Manitoba Hydro, said the research is useful for rural farmers. “Our main interest is to look at ways of becoming more energy efficient,” he said. Agriculture, Food and Rural Initiatives Minister Rosann Wowchuk, who toured a number of greenhouse facilities in the area on Aug. 25, said there is a need for such a vegetable market in Manitoba.

“We import an awful lot of vegetables and if through a greenhouse you can extend the growing season at a reasonable cost, I believe there’s opportunities there,” she said.

Wowchuk noted the advantages of Liu’s project. “If he could extend it to year-round, that would be very good,” she said. “If you can extend the season by a few months in Manitoba, that’s also very good. I was very impressed with what he is doing and I see that as being a technology that other people can adapt to as well.”

Liu got his start growing up on a vegetable farm in China and later graduated from university as an agricultural scientist. He also has a Master’s degree in genetics from the U.S. He moved to Winnipeg in 1996 and worked in Portage la Prairie at Manitoba Crop Diversification Centre in 1997 where he was the manager of the oriental vegetable project.

He said he began working on his greenhouse project at that time. He finally decided to set up his own solar-energy greenhouses in Elie about a year ago, lured by the advantage of a good location close to major markets. “I send them to Winnipeg, to Saskatoon and to Calgary,” he said. Liu said when the rainstorms came in June and July, he had no worries. “Especially this year when we had bad weather, we had a blanket for the greenhouse and it was good weather. There was no flooding. No natural disaster,” he said. “I’m happy with that.” Liu said he hopes his idea can grow just like his hothouse flowers. “It’s easy to transfer the technology from China to Canada and let everybody use it,” he said.

Liu said Wowchuk was thrilled with the U of M research demonstration. “She’s very excited with that,” he said. “She asked me to build more greenhouses. She said it’s an amazing thing, and it’s the only one in Manitoba, maybe Canada.” Liu said it made the most sense to him to start his concept in this province, adding Manitobans shouldn’t have to rely on Vancouver, Ontario or the United States to supplement their vegetables. “Manitoba is an agricultural province,” he said. Liu added he simply got tired of spending the winter doing nothing when the farm was in a deep cold. He wanted to farm all year around. So, developing the perfect greenhouse was the way to go.

“I worked in a lab for 15 years,” he said, smiling. “I got tired of sitting.”

Liu said having a winter production of vegetables is also a lucrative idea.

“You could make $500 a week on a crop you pick every week,” he said. “There’s good money on that.”

The future outlook looks rosy. Liu plans to open his own grocery store for his greenhouse produce at Markham Professional Centre in Winnipeg on Sept. 15.

“I’m very happy,” he said, as he held up a fresh squash to examine.

Gay Mounties Tie The Knot

By Alison Ault

From CNEWS

YARMOUTH, N.S. (CP) - Ronnie Devine doesn't know what the fuss is about. While cleaning his lobster boat Friday, the fisherman said he doesn't understand why people are still talking about the marriage of two gay Mounties in this bustling fishing port.

"It doesn't bother me one bit," he said as other fishermen were busy getting their boats ready to set sail.

"As long as they're doing their jobs properly, I couldn't care less about it."

The marriage Friday of the two Nova Scotia constables, held during a private ceremony at a downtown hotel, marked the country's first same-sex marriage between male Mounties in their trademark scarlet tunics.

Constables Jason Tree, 27, and David Connors, 28, recited their own vows before a justice of the peace and about 100 guests.

But the function was strictly off limits to the public.

A sign at the hotel read: Private function by invitation only. Staff at the front desk refused to talk about the event, and a screen made of white sheets was set up to keep onlookers from seeing anyone moving between the lobby to the convention centre where the ceremony was to be held.

Ken Spragg, a guest at the ceremony, called the wedding another step toward gays being treated like everyone else.

"I got to see them take the vows that other people have taken for granted," he told reporters after the service. "So many don't understand what it means to have that opportunity."

Spragg said the fact the gay couple can do what everyone else can do "is really gratifying."

Russell Robichaud, another guest, said the service was relaxed and Tree and Connors looked great in their uniforms "and couldn't stop smiling."

The couple has said they never intended to stir up controversy.

Tree admitted to being flummoxed by the steady stream of calls from well-wishers and media outlets across North America.

"I fail to see why it gathers the attention it does," he said in an interview days before the ceremony.

"It's something I'd like to keep private."

He refused to reveal any details and requested that reporters stay away. Still, about dozen journalists and photographers staked out the ceremony but were not allowed in and never got a glimpse of the couple.

People in this community of 8,000 seemed nonplussed by the event.

Most townsfolk groaned, laughed and then rolled their eyes when asked about the couple, who have been nicknamed the Brokeback Mounties.

"It's not really for me, but that's their business," said an elderly man who didn't want to be named.

One man strolling past a coffee shop on Main Street said he wasn't sure what to make of an issue that has been a hot topic of conversation in a town best known for its prized lobster fishery.

In the end, he said, it didn't sit well with him.

"I'm an Adam and Eve kind of guy, but if you want to go and do that, go and do it on your own," he said, refusing to give his name.

But others said they were pleased for the couple, who have been together for more than eight years and have patrolled the area for years.

"It don't bother me," said Daniel Doucette, 59. "They've got a job and they've got to work just like us and if they want to get married, that's up to them."

Liberal MP Robert Thibault, who represents the area, congratulated the couple and praised their courage for proclaiming their love so publicly. He said he hasn't heard complaints from his constituents.

"I wish them very well," he said. "The total number of calls to my office expressing concern has been zero. The community seems to have accepted it."

Gay-rights activists have latched onto the story, hoping the marriage will make people across the country look differently at the stereotypically rugged Mountie - an icon in Canadian lore.

Politicians have stepped into the fray as they prepare for a free vote this fall on the issue of same-sex marriage after it was recognized by Parliament a year ago.

Prime Minister Stephen Harper has said he will hold the vote to determine whether there is an appetite to revisit legislation giving homosexuals the right to marry.

In a bid to avoid controversy, Harper recently muzzled his MPs, ordering them not to comment on the marriage of the two Mounties.

Tree has said he had no interest in making a political statement. Still, he said he would be pleased if his marriage helps other same-sex couples come forward.

"I certainly like the positive message that's out there because if we can help one person deal with their relationship or their sexuality, that's great, but our goal was to get married," he said.

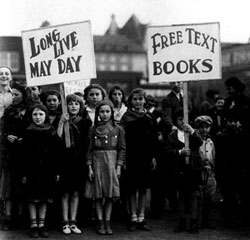

What You Need To Know About May Day

For more than 100 years, May Day has symbolized the common struggles of workers around the globe.

By Leo Panitch

From Canadian Dimension

The seeds were sown in the campaign for the eight-hour workday. On May 1, 1886, hundreds of thousands of North American workers mobilized to strike. In Chicago, the demonstration spilled over into support for workers at a major farm-implements factory who’d been locked out for union activities. On May 3, during a pitched battle between picketers and scabs, police shot two workers. At a protest rally in Haymarket Square the next day, a bomb was tossed into the police ranks and police directed their fire indiscriminately at the crowd. Eight anarchist leaders were arrested, tried and sentenced to death (three were later pardoned).

These events triggered international protests, and in 1889 the first congress of the new socialist parties associated with the Second International (the successor to the First International organized by Karl Marx in the 1860s) called on workers everywhere to join in an annual one-day strike on May 1 — not so much to demand specific reforms as an annual demonstration of labour solidarity and working-class power.

May Day was both a product of, and an element in, the rapid growth of new mass working-class parties in Europe — which soon forced official recognition by employers and governments of this “workers’ holiday.”

But the American Federation of Labor, chastened by the “red scare” that followed the Haymarket events, went along with those who opposed May Day observances. Instead, in 1894, the AFL embraced president Grover Cleveland’s decree that the first Monday of September would be the annual Labor Day. The Canadian government of Sir Robert Thompson enacted identical Labour Day legislation a month later.

Ever since, May Day and Labour Day have represented in North America the two faces of working-class political tradition, one symbolizing its revolutionary potential, the other its long search for reform and respectability. With the support of the state and business, the latter has predominated — but the more radical tradition has never been entirely suppressed.

This radical May Day tradition is nowhere better captured than in Bryan Palmer’s monumental book, Cultures of Darkness: Night Travels in the Histories of Transgression [From Medieval to Modern] (Monthly Review Press, 2000). Palmer, one of Canada’s foremost Marxist labour historians, has done more than anyone to recover and analyze the cultures of resistance that working people developed in practicing class struggle from below. Palmer is strongly critical of labour-movement leaders who have appealed to those elements of working-class culture that crave bourgeois respectability.

Set amid chapters on peasants and witches in late feudalism, on pirates and slaves during the rise of mercantile imperialism, on fraternal lodge members and anarchists in the new cities of industrial capitalism, on lesbians, homosexuals and communists under fascism, and on the mafia, youth gangs and race riots, jazz, beats and bohemians within modern U.S. capitalism, are two chapters that brilliantly tell the story of May Day.

One locates Haymarket in the context of the Victorian bourgeoisie’s fears of what they called the “dangerous classes.” This account confirms the central role of the “anarcho-communist movement in Chicago [which] was blessed with talented leaders, dedicated ranks and the most active left-wing press in the country. The dangerous classes were becoming truly dangerous.”

The other chapter, a survey of “Festivals of Revolution,” locates “the celebratory May Day — a festive seizure of working-class initiative that encompassed demands for shorter hours, improvement in conditions, and socialist agitation and organization” — against the backdrop of the traditional spring calendar of class confrontation.

The other chapter, a survey of “Festivals of Revolution,” locates “the celebratory May Day — a festive seizure of working-class initiative that encompassed demands for shorter hours, improvement in conditions, and socialist agitation and organization” — against the backdrop of the traditional spring calendar of class confrontation.Over the past century communist revolutions were made in the name of the working class, and social-democratic parties were often elected into government. In their different ways, both turned May Day to the purposes of the state. Before the end of the twentieth century the communist regimes imploded in internal contradictions between authoritarianism and the democratic purpose of socialism, while most social-democratic ones, trapped in the internal contradictions between the welfare state and increasingly powerful capital markets, accommodated to neoliberalism and become openly disdainful of “old labour.”

As for the United States, the tragic legacy of the repression of its radical labour past is an increasingly de-unionized working class mobilized by fundamentalist Christian churches. Canada, with its NDP and 30-per-cent unionized labour force, looks good by comparison.

Working classes have suffered defeat after defeat in this era of capitalist globalization. But they’re also in the process of being transformed. The decimated industrial proletariat of the Global North is being replaced by a bigger industrial proletariat of the Global South. In both regions, a new working class is still being formed in the new service and communication sectors spawned by global capitalism (where the eight-hour day is often unknown). Union movements and workers’ parties from Poland to Korea to South Africa to Brazil have been spawned in the past 20 years.

Two more books from Monthly Review Press — Ursula Huw’s The Making of a Cybertariat (2003) and the late Daniel Singer’s Whose Millennium? Theirs or Ours? (1999) — don’t deal with May Day per se, but capture particularly well this global economic and political transformation. They tell much that is sober yet inspiring about why May 1 still symbolizes the struggle for a future beyond capitalism, rather than just a homage to the struggles of the past.

Grassy Narrows

By Macdonald John Enoch Stainsby

From

The Forth World is Right Here

Surviving the nation called Canada

2005

Many years before the arrival of the white man to the land of the Anishinabe Nation, there was a prophecy that when the white people arrived, they would bring the destruction of the forests and the land that sustains the Anishinabe people. When Montréal-based Abitibi Consolidated began logging the land in the late 1980's, the sound of the machines were enough to cause great concern for many elders.

Years of massive clearcutting took a serious toll on the Anishinabe population living in Grassy Narrows. In 1996, members of the nation decided that it was time to try and do something about it.

Initially, Abitibi held open houses and public gatherings in the nearby settlement town of Kenora, Ontario. In an attempt to deal with the loss of forests to Abitibi, some concerned Anishinabe people attended the consultations and tried to have conversations with Abitibi. The concerns of Indians living with the land were not addressed. Several more steps marked a slow but inevitable escalation. When Abitibi held shareholder meetings, some Anishinabe set up protests and pickets outside; letters were written, petitions were signed.

These were either ignored or treated as a minor nuisance. Meanwhile, the centuries-old prophecy took on a deadly accuracy.

For many years, logging went on in the Whiskey Jack forest without much concern. People knew the loggers were working there - people who were going to tend their traplines would often hitch rides on back roads with truck drivers for logging operations. At the time, the logging was selective and not deeply damaging; the operations did not directly gouge the land.

When Abitibi introduced clearcut logging practices to the area, however, the devastation to the entire ecosystem was immediately apparent. When an forest is clearcut, nothing is left except a few trees deemed not profitable enough to cut by the corporation. Mosses, mushrooms and the soil itself are torn up, leaving giant patches of barren land.

"I'm not against logging," says Joe Fobister of the Anishinabe Nation. "I'm against how they're doing it, and who is doing it, making millions of dollars off of our land and leaving us nothing."

"This land is so wealthy. It's our land, and yet we remain the poorest of the poor."

This view is not a monolithic one. The youth who have often taken the lead in saving the Whiskey Jack forest, carried a simple slogan: No negotiations, no compensation, no more clearcutting.

The reason for the first part of the quote is that A) Abitibi wanted to talk while continuing to work in the Whiskey Jack forest, and B) the negotiations that were being proposed involved corporations such as Abitibi given equal say to the nations Canada and the Anishinabe, inherently giving them nation-level legitimacy, something that many people from Grassy Narrows reject.

Part of the blame, says Fobister, should be laid at the feet of a band council that acts on behalf of the settler state of Canada.

"The council and the chief make a good living, and get a very good income. In this very poor community, that's why people join the council. They have no real power, but they are scared to risk their funding," he explains. This dynamic — the creation of a de facto ruling comprador class of Indians to implement colonial expropriation of resources — is an all-too-familiar refrain in Nations that resist the assimilationalist policies of Canada and refuse to give up their land to corporations like Abitibi.

Fobister continues: "They are not there for the good of the people, but simply for an income."

The entire Whiskey Jack forest is part of the homeland of the Anishinabe Nation. As Abitibi has progressed, the land has been weakened. To date, slightly more than half of the Whiskey Jack forest has been destroyed.

"When they destroy the land, they are attacking my spirituality," explains Fobister. He explained to me how deer like the grasses that grow in areas that have been recently clearcut, and they release excess amounts of droppings in the area. That enters the water, which the moose drink it, acquiring a brain disease very similar to mad cow. People in the nation will likely eat these moose, with as yet unforeseen effects.

"I used to be comfortable in the bush, but I'm not anymore," says Fobister. "The bears are acting very strangely and are no longer afraid of people; they don't just run away when they see you."

Meeting with people on the reserve, the greatest threat to the health of the nation becomes apparent. Clearcut logging causes massive soil erosion, and this in turn releases a normally non-threatening natural form of mercury. This mercury ends up in the water - the water supply of the reserve, as well as in the animals, fish in particular. The nation depends on the land, eating and harvesting the animals and fish as they have for thousands of years.

"Some people have the shakes. [This one elder], his arm shakes badly when he's trying to do something and he can't stop it. You can also lose your sight [from the mercury]. The ones who trap and fish off the land get it especially," explained Ashopenace. "We take it very seriously when someone loses a trapline [to clearcuts] or when more contamination comes in. We hear that more mercury is supposed to come by soon."

Here, one can witness the poisons draining the life out of the people, one at a time. The Canadian and Ontarian governments have done nothing to address the poisoning effects and the ecological devastation caused by the clearcutting.

Several women from the nation delivered an ultimatum to Abitibi workers inside the Whiskey Jack forest in February 2003. After protests at the Montreal head office of Abitibi did not elicit any response, some members of the community decided to symbolically demonstrate their power to the corporate giant. A plan was launched to blockade the logging roads where Abitibi had access to the forests. Several women from the nation delivered a notice: if you have not evacuated the forest by 5pm tomorrow, you will be blockaded in and you will not get out. The workers left.

The Anishinabe youth have been among the strongest voices advocating for the rights of the Nation and the preservation of both the land and their traditional means of using it. They argued persuasively that a one-day symbolic protest and blockade would not be enough to deter Abitibi in any real way. They argued for a complete shut down of the forest roads period, thus bringing an end to logging - at least for the time being.

Ashopenace remarked: "We [the youth] already wanted to do something more, we knew that one day wouldn't be enough. We wanted to do more damage. [Now] we are slowing them down and reducing their profits."

It was only after a year of round-the-clock rotating blockades that Abitibi saw a need to talk to the people who live in Grassy Narrows.

"We fed them and tried to get them to relax, but you could see they were still very nervous to be here," explains Ashopenace.

He described the corporate representatives' defence of their logging practices. "Abitibi said they are trying to provide economic development for the community," he said. "It was hard to hear the debate because the youth were openly laughing at how ridiculous the arguments were. The argument was that Abitibi doesn't have obligations because the treaty [Treaty 3] was between Canada and Anishinabe and had nothing to do with them." When it comes to responsibility for the poisoning of the community, their food supply, the animals and the land itself, "Abitibi blames a paper mill that comes out of Dryden [approximately 200 kilometers away from Grassy Narrows] and says 'you need to talk with them.'"

The Ontario Ministry of Natural Resources has the official responsibility to uphold environmental regulations. While MNR holds jurisdiction, regulations hold that almost all mining, forestry, oil drilling and similar resource extraction work is "assessed" by the very same company that wishes to dig, drill, cut and so on.

In Canada, the fox is in charge of the henhouse.

Treaty 3 was signed by Chief Saskatcheway, previous to the Indian Act, and therefore from the traditional, non-hierarchical political system that many nations including the Anishinabe practiced before the imposition of the band council system. It was not interpreted or understood by the nation — who then decided on such matters by consensus - as a surrender of title or land. To this day, the elders maintain that they would not have signed any such treaty.

The legacy of Treaty 3 is still disputed. Yet, not even the Canadian government's own interpretation of the treaty is honored. Members of the Nation are trying to challenge the rights of Ontario, Abitibi or Canada itself to claim the Nation's land for themselves.

Fobister spoke about dealing with Abitibi about this challenge: "They are afraid that if we can control our land, if we can prove it is ours and always has been, that this will mean the same thing elsewhere, that then other nations will follow."

"I told them that that's their problem, not mine," he added.

The idea of having talks at all with Abitibi— rather than the state of Canada—continues to be problematic. Many nationals point out that even talking to Abitibi at a table that includes both the nations of Anishinabe and Canada confers on a forestry corporation the same say as a nation. The only legitimate talks, say many Anishinabe, would take place between the nations and governments who make laws.

But for the Canadian government, it appears that Nation to Nation talks between the Anishinabe and Canada must be avoided at all costs. If Abitibi were accountable to the law of the land as negotiated between Nations, it would establish the de facto existence of the Anishinabe as a Nation. Judging by the government's across-the-board intransigence in sovereignty negotiations, this would be a worst case scenario for the colonial state. But talks have continued, meetings still get held and money is even accepted in the short term from Abitibi here and there, in exchange for continuation of operations.

"Those who want a deal are operating for today, just to get the money, and not even that much money really," explains Judy Da Silva. "It is the youth and others who blockade that are thinking long term, thinking about the future, about preserving the forest, our traditions with the land and our way of life."

Roberta Keesick makes the case more bluntly.

"The government wants us off the land, they want us to be assimilated," she stated. "They don't want us to be who we are."

Ashopenace explained the dynamic.

"With the destruction of the forests, it's our whole way of life and culture that's getting sick," he explained. He described areas in the Whiskey Jack forest that might hold the key to the ancient history of his people.

"[In the Whiskey Jack Forest] there are some historical rock paintings that are thousands of years old. These are in areas we call virgin land. If Abitibi continues doing what they are doing, with their roads, their cutting and so on, we might lose these."

His assessment is severe.

"What Canada is doing is ignoring us when we try to bring attention to how our rights are being violated. The world needs to open their eyes as to how Canada really is."

Many say there are only three options to deal with the social problems and poverty of the Nation. First, people could accept the clearcutting as "economic development", and try to secure temporary work while the land and their connection to it is decimated. Second, they could try to develop eco-tourism as a means of using their knowledge of the land as a way to bring in much needed dollars, but at the rist of commercializing their own history and reducing themselves once again to a secondary role in their own woods and waterways. The third option is to remain as things are, with people living subsistence lives with no jobs and little income.

A fourth option defies orthodoxy, but is becoming more appealing as the situation deteriorates with little recourse for those stuck in a colonial system of governance. The people could take control of their lands back from the Canadian state and assert their right to self-determination, in accordance with prior treaties and international law on the preservation of National culture. This fourth option involves nothing short of decolonizing the Nation of Anishinabe.

For anyone who visits, it is clear that the process is already underway.

One of the most remarkable changes to come from the last few years of blockades has been the increased self-confidence of the Anishinabe people. By taking matters into their own hands, they have taken back a modicum of control over their own destiny.

The area near where the main blockade was originally established is now a common gathering place for many purposes, whether praying at the sacred fire in the wigwam or to roast wieners on the large open firepit a few feet from the site of the first blockade.

I was sitting by that firepit one night with an eight-year old girl from the Nation, and I asked her a few questions.

"How do you feel about the blockade?"

"I feel good," she answered.

What do you want Abitibi and the government to do?"

"I want them to stop logging."

"What do you think will happen if they don't stop logging?"

"Then my mommy will have to keep on warring," she said.

Then abruptly, she got out of the chair and ran off to play with other kids and her puppy. As the sun set near the blockade, the roar of the machines of Abitibi remained absent from the Anishinabe Whiskey Jack forest for another day. And the sun always rises again.

It Took Them 400 Years to Find Us Again

Agribusiness firms wallow in profits, farmers in losses

By Paul Beingessner

From CCPA Monitor

2006

About six years ago, I met with a group of farmers in Gravelbourg, a mainly French community in southwest Saskatchewan. The small talk before the formal gathering turned to the sorry state of the farm economy at the time. An older farmer shook his head in disgust. “My ancestors,” he recalled, “came from France in the 1600s to get away from the rich and powerful people who were exploiting them. Now, after all those years, look what we’ve come to!”

There was a moment’s silence. Then one of the other farmers said jokingly, “Well, it only too them 400 years to find you again.”

Everyone laughed, but it was an uneasy laugh. That simple but profound remark has stayed with me. And as the farm economy has gone from bad to worse since then, I’ve thought about it a lot. Viewing some statistics recently put together by the National Farmers Union reminded me again.

The figures were the profits reaped by businesses involved with agriculture in 2004. It was striking to see how great a year 2004 was for agribusiness. A partial list of the companies that made record profits that year includes- Imperial Oil, Saskferco, Pfizer, Novartis, Deere and Company, the Bank of Nova Scotia, Cargill, Tyson Foods, Anheuser-Busch, Canadian National Railway, Kraft Foods, ConAgra, General Mills, Kellogg Co., Maple Leaf Foods, J.M. Smucker Co. (Robin Hood), Prairie Malting, Bunge Ltd., Molson/Coors Brewing, Sun-Rype Products, Saputo Inc., Loblaws, and McDonald’s.

Profits for these companies ranged from $12 billion for Kraft Foods and $14 billion for Pfizer to a mere $1.3 billion for CN. Return on equity ran from 83% for Anheuser-Busch to only 18% for ConAgra.

Canadian farmers had a different year in 2004. Collectively, they lost $7.7 billion, and saw their return on equity at minus-5.09%.

It would appear that they have indeed found us again.

All of which led me to think about the beginnings of agriculture. Farming began in what is now Iraq—the Fertile Crescent—about 10,000 years ago. At that time, people who had previously been hunters and gatherers settled down in villages and began to cultivate the soil and grow crops.

Ten thousand years might seem like a long time. But if you put it in terms of generations—a generation being about 30 years—that represents about 300 generations of farmers. Between my father, my grandfather, and myself, we represent three generations. So, if you look back in time in a straight line, you could say that I’ve known 1% of all the generations that have ever farmed. That’s an amazing number.

And what did farmers do in those 300 generations? Well, they developed modern crops. By careful selection, they turned tiny seeds of grasses and small wild fruits into grains and fruits and vegetables, many of which we still grow and eat today. They developed hundreds of breeds of cattle, sheep, goats, and other animals suited to a wide range of climates around the globe. And they did all this before the discovery of the science of genetics, which is just a bit over 100 years old.

You can see that farmers in those 300 generations were very busy. Imagine the progress that had to be made in each generation! That knowledge, both explicit and implicit, was passed from parent to child 300 times. The explicit knowledge concerned how to choose the best seeds for next year, how to tend animals, when to harvest crops, how to store them—a million pieces of knowledge passed down by word and example. And the implicit knowledge was also shared. It contained the genetic storehouse built up generation by generation, carrying the germ-plasm of superior plants and the genes of superior animals.

For 300 generations, 10,000 years, farmers kept this knowledge and passed it on. And now, in our generation, the chain is being broken. Farmers are leaving the land in droves. Why? Because we gave up our control over that knowledge. As modern science evolved, we gave it to the universities. But they were publicly owned, and, as they improved on that knowledge, they gave it back to us—freely.

Then, about 20 years ago, there was a dramatic shift. Governments decided that knowledge should no longer be free. They brought in plant breeders’ rights and patents on living things. Now, by adding one tiny jot to the information that came from 300 generations of farmers, private companies can own all this accumulated knowledge. And once they owned it, they began to sell it back to us—but to use, not to own. Now farmers are prohibited from saving their own seeds and sharing them with their neighbours, as they had done for millennia.

But we did this for a reason, right? We did it because science and the privatization of knowledge were going to give us better crops, make us better off, allow us to feed the expanding global population. Oddly, however, 400 million people still die of hunger every year, and a billion others have inadequate diets.

Farmers all over the world are in trouble, fleeing to overcrowded cities and abandoning the way of life of 300 generations. Canadian farmers suffer new record losses while agribusiness thrives off our work. As the NFU has wryly noted, “Farmers are now the hamsters in the wheel that runs the agribusiness empire. The solution to the farm crisis, we’re told, is for the hamsters to run faster.”

So we look for solutions: ethanol, bio-diesel, hog barns, higher-yielding crops, the World Trade Organization. All these things may hold promise. But, until we realize that they’ve found us, such technical or structural improvements will only add to their wealth, no matter how fast we run on our hamster wheels.

(Paul Beingessner is a consultant, writer, and third-generation prairie farmer. He raises sheep, cattle, and a little bit of hell from Truax, Saskatchewan.)

Stuff pity!

People with disabilities want to get on with their lives. Others keep standing in the way. Dinyar Godrej explores what this can mean in the Majority World.

From New Internationalist

With his wedding date approaching, Samuel Kabue of Nairobi, Kenya, remembered a past kindness. There had been a man who had intervened when as a child he’d been run over by a cyclist. This man had apprehended the cyclist who tried to flee from the scene and then took the time to get Samuel to his mother. Later Samuel began visiting the man’s bookshop, first on his own, and then, with the onset of his blindness, with someone to guide him.

Now Samuel stood in front of him with an invitation card. ‘With all the excitement of anybody who would have been in my position at the time, I presented him with the card. I was very embarrassed by his reaction. He kept quiet for a while and then said to me, “Why do you want to give yourself more trouble in life? You are already blind, how are you going to handle the burden of marriage?”’1

In Mumbai, a disabled activist using a nom de plume began writing about sex – a fenced-off area in her life, the existence of which is constantly denied by other people. Even other disability rights activists gave her short shrift when she once plucked up the courage to bring up the subject. She was scorned for entertaining a ‘Western obsession’ and told that there were far more important things people with disabilities had to fight for in a country like India.

Also in India, Firdaus Kanga was coming to terms with what he thought was his difference. He’d been born with brittle bones which left him as a boy hesitant to break a biscuit. ‘There was something about the sound, the snap, that always reminded me of those moments when I would crack a rib or break a hip, which happened almost as often as the festivals that sprinkled the Indian calendar.’ The ‘difference’ he was contemplating was his homosexuality – a subject so taboo in polite Indian society that he had never heard anyone talk about it.

‘ Homosexuality was the different part of me that gave me pleasure, allowed me to hug my body – if rather gingerly – rather than fear it, fear the pain it brought me, an unwelcome present I could not refuse.’

In his twenties he wrote a novel, Trying to Grow, whose success allowed him to move to London. Here he was to find ‘one very special love’ – with someone who had Tourette’s Syndrome, an unexplained condition characterized by compulsive activity. ‘Sometimes just being able to sit down took him the best part of an hour. Somehow we found the comedy between that and the fact that I could never stand up. We also found a tenderness that I have never known before or since – tenderness and desire fulfilled.’

While unfortunately, for far too many people, love remains a thirst that is not slaked – with little relation to integrity of character or perceived goodness – what is remarkable is that people with disabilities are often denied at the outset the right to participate in this particular lottery of life.

In the West, this has resulted in an extensive literature of anger railing against assumptions of asexuality made about disabled people, exclusion from sex education at school, ‘protection’ from such things by self-appointed ‘guardians’ (an infantilizing concept if ever there was one), misinformation about the body’s capacity for enjoyment when that body happens to differ from the ‘norm’, curtailment of one’s reproductive rights and general disapproval when creating a relationship. ‘Stuff that!’ is the message, in short, from many people with disabilities living in the rich world who have written about their experiences. There is a herculean amount of struggle behind that position. But in the Majority World there is a corresponding silence.

It’s not that love – and its sexual expression – is not a pressing concern for people with disabilities in the Majority World. How could it be otherwise? But too many other people seem to think it doesn’t matter, or is a thing of shame that disabled people should suppress. If this treatment strikes you as less than human, you’ve got the point.

But perhaps love and sexual expression do have to make way for even more pressing concerns.

When Samuel Kabue visited England he met up with a woman with a disability, who complained to him about her Meals on Wheels service never being delivered on time. ‘It struck her as an infringement of the right of recipients to eat at the right time. As I thought about the situation in my country, my reaction to this complaint may not have pleased her. I said to her that in my country, it would not matter whether the meal was brought in the middle of the night or at any hour, it would still be most welcome. Many of our disabled people go for days without any meal, and even when they get it, it is hardly what would be called a “meal”. When you hear that people are dying of hunger in parts of Africa, people with disabilities will have died long before that.’

Blocking out ‘bad karma’

Disabled people are disproportionately poor all over the world. But in countries where poverty is not in the slightest bit relative, it robs them of all the chances that mainstream society is so intent on withholding anyway. About 82 per cent of disabled people live below the poverty line in the Majority World. The World Bank states that ‘half a billion disabled people are undisputedly amongst the poorest of the poor’ – out of a total estimated worldwide disabled population of 600 million. Survival is often their most pressing human rights issue. Death rates for children with disabilities are in some countries as high as 80 per cent – no-one knows how many of these children have been murdered.

Out of the thicket of definitions available for the word ‘disability’, the valid principle for disability movements is singular. Disability for them isn’t primarily about the physical, mental or intellectual impairments that are associated with it, but about society’s prejudiced response. Disability is a critique of social organization that seeks to exclude, restrict and put at a disadvantage people who have impairments, instead of recognizing the diversity of human beings and their essential equality. Put more simply, it is about prejudice. When that prejudice pushes you to the back of the queue in a refugee camp or denies you food when it’s scarce, it can be lethal. For example, many parties in the aid response to the tsunami had no clue how to respond to the needs of disabled people affected by the disaster and those newly disabled by it.

The social barrier faced by people with disabilities can be huge, particularly in the Majority World where activism for rights, by and large, has a much shorter history. What would it take to break down the walls? A UN working group which has the input of several Disabled People’s Organizations (DPOs) has been busy drafting a ‘Comprehensive and Integral International Convention on the Protection and Promotion of the Rights and Dignity of Persons with Disabilities’.

It has articulated a sound set of basic principles: ‘dignity, individual autonomy including the freedom to make one’s own choices, and independence of persons; non-discrimination; full inclusion of persons with disabilities as equal citizens and participants in all aspects of life; respect for difference and acceptance of disability as part of human diversity and humanity; and equality of opportunity’. This sounds just the ticket – though the US, in time honoured fashion, has indicated it won’t sign up and is encouraging other countries to follow its lead. There are, moreover, already rumblings from poorer countries that they may have problems finding resources to support their disabled citizens in realizing their capabilities.

The lack of resources argument is a compelling one, but the question that does need to be asked is whether it is being used as a justification for unequal treatment, the kind which is so routinely meted out by society at large. In recent years, the growing disability movements in the West have been reaching out to disability groups in the Majority World to lend support to their struggle for an equal claim on society.

Society needs a considerable amount of pushing before changes begin to register. Cambodia currently has the second highest rate of disabled people in the world (Angola has the highest) – a legacy of years of war and extensive use of landmines. With this recent surge in physical impairments, a corresponding cultural response might have been expected. But Cambodian society stuck fast – clinging to notions of ‘bad karma’, blaming the sins of people’s past lives for their disabilities. Oum Phen, a young landmine survivor, described the prevailing attitude: ‘People didn’t treat me like a human being. They looked down on me because I couldn’t support my own family.’ So when disabled people in the country began to organize in self-help groups (with some prompting from the British organization Action on Disability and Development), new members often felt there was nothing they could do to change society. But by working together they managed to overcome this prejudice by getting the skills to earn an income. They also targeted people who could make a difference – persuading some Buddhist monks to include scientific explanations of disabilities in their sermons to fight the grip ‘bad karma’ had on society.3