Art: For the Common Delight

by Dee Axelrod

From Yes!

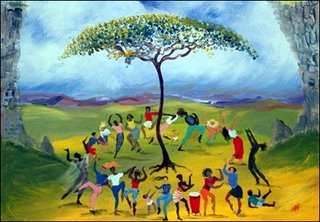

After a century of art for art’s sake, art in the last decade has been increasingly giving voice to the silenced, illuminating complex political issues, and bringing joy to the public square.

While the last 10 years have seen the weakening of funding to individual artists and the end of many alternative venues for showing art, a global art scene is thriving. The broadening and democratization of mainstream art, largely driven by the Internet, has helped reshape the aesthetic landscape from a New York-centric, gallery-driven scene to a thriving online global arts community.

In 1995, widespread access to the Internet produced a dazzling explosion of opportunities for artists to connect with practitioners from all over the world. Suddenly, in a single afternoon, an artist could “visit” a Prague printshop, view the Conesisters’ collection of early Modernist works at the Baltimore Museum, chat with a collective of feminist artists in New Zealand, submit work to an abundance of shows worldwide—or show and sell from her own website.

The Internet has created not just virtual art spaces but new opportunities for showing physical art in the real world, giving new scope to DIY (do it yourself) ingenuity. A traveling exhibit, for example, that would once have been organized by curators might now be artist-created and controlled—and feature works from all over the world.

One such show, organized online, opened in Milwaukee in 2001, featuring mixed media works ranging from Chicago artist Carlos Cortez’ woodcut posters for Industrial Workers of the World (I.W.W.) to Beehive Design Collective artists Kehban Grifter and Juan Manchu’s images in collaboration with several Colombian communities. By August 2005, the exhibit had been shown in 27 cities and traveled more than 25,000 miles, aided by a website, www.drawingresistance.org, that became a virtual gathering place. “Drawing Resistance” depended on publicity and fund-raising from each local venue.

The capacity to stay connected online has helped power a healthy diaspora of artists to places besides New York, just as the Internet emphasis on communication has encouraged artists toward collective art activities that make an end run around market influences.

It has also encouraged new forms of arts education. The Beehive Collective (www.beehivecollective.org), an ongoing, decentralized collaboration of anonymous “bees,” has made it its mission “to cross-pollinate the grassroots” by producing images that anyone is free to take and use. Among other projects, the “hive” delivers some 200 lectures per year on globalization and promotes collaborations between the visual and literary arts.

Community arts programs—curricula for teaching a more socially engaged art—emerged at such campuses as the Institute for Social Ecology and Goddard College, both in Plainfield, Vermont.

A group of 60 “eco artists” who gathered at the 1998 College Art Association meeting in L.A. formed an ongoing network of artists concerned with preserving and restoring the natural world.

One such project, completed in June 2005, is “Three Rivers Second Nature”—an analysis of three river systems and 53 streams of Allegheny County, Pennsylvania initiated by Carnegie Mellon University’s Studio for Creative Inquiry. A team of artists and researchers, headed by Tim Collins and Reiko Goto, synthesized information gathered from historians, landscape architects, geographic information systems specialists, botanists, engineers, and water-policy experts to map the region’s natural history, analyze water use, and consider stream restoration. On completion of the project, the team presented their findings to the public.

Meanwhile, the traditional notion of public art—a discrete object made without much consideration for a particular place—has undergone a transformation that reflects artists’ deepening understanding of what it means to work in community.

Artists first began to take into account the history and ecology of a particular site in the early 1970s. A natural next step was to consult with community members, perhaps eliciting their ideas and even some contributions. Over the last decade, a public art has emerged that seeks to place the creative process wholly in the hands of the community, with the artist in the role of facilitator, helping to draw forth a community’s stories. Community has been defined broadly to include such marginalized groups as inmates and shelter inhabitants.

But of all recent developments, it may be the emergence of artist-activists in their 20s that is most exciting. A different breed from past art school graduates competing to become “art stars,” these young people make art in service to social change. They do “reclamation art” projects at degraded sites. They help create dialogue among polarized groups. They work to foster a sense of community.

They are the hopeful future of art.

Related Web Sites

www.ecoartnetwork.org - A Web site dedicated to ecological art and the artists who create it. Here you can find sites of the artists participating in the movement.

www.greenmuseum.org - More resources on the culture of eco-art and the people who practice its ideals. Lots of information, including interactive WIKIs for educational resources and discussion groups.

www.artsforchange.org – Using art as a tool for healing and social change. The creation of Beverly Naidus.

www.communityarts.net – Promoting information exchange, research and critical dialogue within the field of community-based art including programs that teach community-based art.

www.goddard.edu – Join an MFA program in Interdisciplinary Arts that has a focus on art for social change, healing, spiritual growth and a required community art practicum.

0 Comments:

Post a Comment

<< Home