Who is hungry in Canada?

FromThe Canadian Association of Food Banks

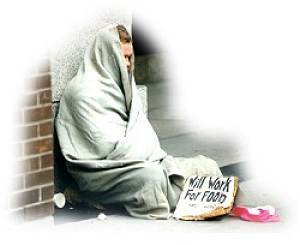

In Canada, hunger is largely a hidden problem. Many Canadians are simply not aware that large numbers of children, women and men in this country often go to bed hungry.

While anyone is at risk of food insecurity at some point in their lives, certain groups are particularly vulnerable:

Welfare Recipients

People receiving welfare assistance as their primary source of income continue to make up the largest group of food bank users. This year, 51.6% of food bank clients in Canada were receiving welfare. This suggests that welfare rates in Canada do not do enough to ensure food security for low-income Canadians. According to the National Council of Welfare, welfare rates across Canada continue to fall below the poverty lines.

Working Poor

People with jobs constitute the second largest group of food bank clients, at 13.1%. Anecdotal evidence in the HungerCount 2005 report shows that the majority of food bank clients with jobs are employed at low wages. The expansion of the low-wage economy has generated more working poor who, even with full-time jobs, are unable to meet basic needs for themselves and their families.

Persons With Disabilities

Those receiving disability support have made up the third largest group of food bank clients in the last four years, according to successive HungerCount surveys. It is just one more example of the broader crisis of inadequate social assistance in Canada. Disability support is clearly not enough to help clients feed themselves. If current disability programs and rates do not improve we expect to see a rise in food insecurity among this demographic, since Canada has a rapidly aging society and life expectancy is increasing.

Seniors

Seniors accessing food banks across Canada is a sad reality. HungerCount 2005 reports that seniors accounted for 7.1% of food bank users in a typical month of 2005. This is an increase from the previous year when 6.4% of food bank clients were seniors.

Children

Children continue to be over-represented among food bank recipients in Canada. This year, 40.7% of food bank clients were under 18. Child poverty has not improved since 1989, the year when Canada made an all-party resolution to end child poverty. Child poverty is directly tied to the level of household income. Among food bank clients, families with children make up more than 50% of recipients.

Lone Mothers

Lone mothers and their children are still one of Canada's most economically vulnerable groups. It is likely that many of the food bank users who are sole parents (29.5%), as reported in HungerCount 2005, are women: according to Statistics Canada, the majority of single-parent or lone-parent families are headed by women (85% or 1 in 4 of Canada's lone-parent families).

Solutions

Hunger, as a symptom of poverty, is a structural problem. Sustainable solutions to hunger and poverty require a mix of system-based policies aimed at improving the incomes and income security of poor Canadians, such as raising social assistance rates and minimum wages, improving access to employment insurance and developing a national child care system. HungerCount 2005 outlines specific public policy recommendations to governments in eradicating domestic hunger.

Benefits for low-income seniors are going up

The Guaranteed Income Supplement (GIS), the Allowance and the Allowance for the survivor are going up 7%. The increase will be phased in over two years. In January 2006, GIS and Allowance payments will go up $18 a month for single seniors and $29 a month for couples. In January 2007, payments will increase again by the same amount. If you think you might be eligible for one of these benefits, call 1-800-277-9914 (toll-free) or contact the regional coordinator nearest you. Fact sheets and posters are also available upon request. For more information on seniors' benefits visit the Service Canada website.

Food bank use by B.C. children up 42 per cent

FromCTV.ca

VICTORIA — A national report on the use of food banks by children in Canada has put British Columbia on its trend watch.

The B.C. Liberal government said it's concerned about the results which found 41.7 per cent more children needed emergency food in B.C. in 2004 over 2003- some 8,000 more kids. Human Resources Minister Susan Brice, however, said the conclusions in the Canadian Association of Food Banks' annual report reflect a North American problem.

The B.C. Liberal government said it's concerned about the results which found 41.7 per cent more children needed emergency food in B.C. in 2004 over 2003- some 8,000 more kids. Human Resources Minister Susan Brice, however, said the conclusions in the Canadian Association of Food Banks' annual report reflect a North American problem. The association's annual national HungerCount survey also found that in Saskatchewan nearly 2,000 more children needed food banks in 2004, an increase of 24 per cent from 2003.

Child Poverty In Canada- An Overview

From Free The Children.org

Many people mistakenly assume that child poverty is a challenge only people in developing countries are facing. This is sadly untrue. In Canada, the situation of child poverty has gone from bad to worse. UNICEF’s report on Child Poverty in developed countries ranks Canada near the bottom for children’s well-being, at 17 out of 23 countries. This is unacceptable for a country that prides itself on being consistently chosen as the best place in the world to live.

• Canada is one of the richest countries in the world. However, about 1,400,000 of its children live in poverty (almost one and a half million). Children of single parents and those of aboriginal descent have suffered the most.

• Children are poor because they live in disadvantaged families. The way to end child poverty is to allow families the ability to support themselves in a meaningful way. The last thing a parent wants is to have their children go hungry.

• Single mothers and their children experience the worst levels of poverty. 81% of single mothers with children under the age of 7 live in poverty. Countries such as Sweden and France provide far greater help to single mothers so that they and their children do not live in poverty.

• Food banks: A U.N. Human Rights committee noted that the number of food banks in Canada grew from 75 in 1984 to 625 by 1998.

• A U.N. Human Rights Committee criticized Canada for adopting policies that have increased poverty and homelessness among many vulnerable groups (such as children and women) during a time of strong economic growth and increasing affluence.

• The federal government says that its Child Tax Benefit helps poor children. But the benefit is far too low and the poorest children are disqualified from receiving it. Children living in families receiving welfare - who are the poorest children in Canada - have the benefit taken away from them by their provincial government. This is wrong and must be ended. Apart from Newfoundland and New Brunswick, the poorest children and their families receive no help from the Child Tax Benefit.

• Children of full-time working parents make up almost 30% of poor children in Canada. Their parents do not get paid a living wage. Workers in developing countries making shoes for Nike or goods for Wal-Mart should be paid a living wage. Workers in Canada should also receive a living wage. In the United States 32 cities have passed bylaws requiring that all city contractors pay their workers a living wage. Perhaps Canadian cities and provinces should be asked to make the same commitment.

• Each province and the federal government have minimum wage laws. All workers must be paid at least the minimum wage. But, taking account of inflation, these minimum wages are 25-to-30% lower today than they were twenty years ago.

The UN Convention on the Rights of the Child (UNCRC)

Canada has ratified the United Nations Convention on the Rights of the Child. In doing so, it is obligated to provide basic human rights to all children. The Convention, for example, obligates Canada to provide an adequate standard of living for all children.

But hundreds of thousands of Canadians are going hungry and have to go to food banks because they do not have enough to eat. It is a sad fact that almost half of the people using food banks are children.

Canada's Charter of Rights and Freedoms

Canada's Constitution includes a Charter of Rights and Freedoms that guarantees every Canadian security of the person. People who live in poverty do not have security of the person. If they live in hunger, their health and their lives are at risk. If they are homeless, they do not have physical or mental security.Poverty means that people do not enjoy their basic human rights.

The UN currently ranks Canada 17th out of 23 industrialized countries – seventh from the bottom – when it comes to child poverty

Child Poverty UN Report

By Mark Nichols

From Maclean's

Candace Warner, a jobless single parent, lives with her sons - two-month-old Keo and 1 ½-year-old Skai - in Winnipeg's run-down Wolseley district. The product of an impoverished background, Candace, 24, struggles to pay the apartment rent and feed and care for her children on about $1,000 a month in social assistance. "My sons need new clothes and things that I can't buy," she says, "because I don't have the money." With Canada's once sturdy social safety net badly frayed, the plight of Candace and her kids is not unusual.

According to a study released last week by the United Nations Children's Fund - UNICEF (the organization long ago changed its name, but kept the old acronym) - 15.5 per cent of Canadians under 18 live in poverty. That relegated Canada to 17th place in a ranking of 23 industrialized nations and prompted demands for action. "Politicians talk about eradicating child poverty," said Jean-Marie Nadeau, executive assistant at the New Brunswick Federation of Labour. "Then they shut their big doors and the young are forgotten."

As it happened, publication of the UN study coincided with a Statistics Canada report showing that a buoyant economy finally pushed 1998 family incomes past levels recorded before the recession of the early 1990s, with after-tax family incomes averaging $49,626. The numbers also showed the gap between low-income and affluent Canadians steadily widening, leaving 3.7 million Canadians in straitened circumstances.

Income disparities figured prominently in the UNICEF study, which estimated that 47 million impoverished children live in the world's 23 richest countries. The report found the lowest rates of child poverty among northern European countries with strong traditions of wealth redistribution. Sweden - with only 2.6 per cent of its children living in poverty - had the lowest rate, while Canada ranked behind France, Germany, Hungary and Japan, but ahead of Britain, Italy, the United States and Mexico, in last place with a 26.2-per-cent child poverty rate.

The sometimes surprising findings were partly due to methodology - the rankings were based on "relative poverty," defined as household income that is less than half of the national median. That meant nations like the Czech Republic and Poland, with high overall poverty rates, came out ahead of Canada, Britain and the United States, where higher average incomes and income disparities make more people relatively poor.

"Canada reflects poorly in a relative measurement," said Marta Morgan, director of children's policy at Human Resources Development Canada, "because middle incomes in this country are quite high." Even so, when social advocacy groups use StatsCan's low-income cutoff as a measure of poverty, they generally estimate there were about 1.4 million poor children in Canada in 1997 - a child poverty rate of 19.8 per cent that is well above UNICEF's.

The study's authors argued that even when children from families with limited resources have the necessities of life, they suffer by being excluded from normal childhood activities. Linda Rowe, a single Halifax mother who stretches aid of about $1,400 a month to support herself and two young sons, knows they are feeling that pinch. "Right now, I'm trying to borrow $20 so my kids can go on a school trip," she says.

With the years of stringent budget-cutting behind them, Ottawa and some provinces have started to rebuild social supports that benefit low-income families. Finance Minister Paul Martin's February budget reduced taxes for families with children and earmarked $2.5 billion in additional funding for Ottawa's child tax benefit, which currently pays up to about $160 a month for children in low-income families. And after nearly three years of wrangling, federal-provincial talks on a proposed National Children's Agenda - that could usher in early childhood development and child-care programs - appeared to be moving ahead, with ministers agreeing to draft a policy framework by the fall.

Even so, some provinces still insist that Ottawa will have to restore billions of dollars in lost health and social funding before the agenda becomes a reality - a stumbling block that could hold up long-overdue measures to help Canada's children.

Poor Kids in Developed Nations

Percentage of children living in "relative" poverty

(household income below 50 per cent of national median):

Sweden: 2.6%

Norway: 3.9%

Finland: 4.3%

Belgium: 4.4%

Luxembourg: 4.5%

Denmark: 5.1%

Czech Republic: 5.9%

Netherlands: 7.7%

France: 7.9%

Hungary: 10.3%

Germany: 10.7%

Japan: 12.2%

Spain: 12.3%

Greece: 12.3%

Australia: 12.6%

Poland: 15.4%

Canada: 15.5%

Ireland: 16.8%

Turkey: 19.7%

Britain: 19.8%

Italy: 20.5%

United States: 22.4%

Mexico: 26.2%

Source: UNICEF

0 Comments:

Post a Comment

<< Home